Television presenter and radio personality Fearne Cotton began her career at the age of 15 in British children’s television. By 2007 she had joined BBC Radio 1 to copresent the chart show and then went on to become a household name with her own morning show on Radio 1. These days, she divides her time between writing books and family life with her two children in South West London. Fearne is married to Jesse Wood, the son of the Rolling Stone’s Ronnie Wood, though she always uses her maiden name professionally. On her paternal side she is related to the former BBC executive Bill Cotton (1928-2008) who was her grandfather’s cousin. He was the son of the band leader, Billy Cotton, a one time big TV and Radio entertainer in the 1950s and 1960s.

Fearne has said, before the Who Do You Think You Are? programme began looking at her roots, that all her professional life she had felt a strong desire to succeed:

I’ve got this drive and it’s a burning drive inside, and I know that comes from my ancestry

Describing her own upbringing as “normal”, she wants to discover a remarkable ancestor or two in order that she might pass on the stories of their lives to her own children.

Fearne begins her delve into her past family by visiting her parents, Mick and Linda Cotton, at home in Buckinghamshire. The TV programme sees them chatting about Viking heritage on Linda’s side being a possibility and they reminisce about Mick’s mother Ruby, who had been born in South Wales. Mick shows Fearne a photo from 1913 of Ruby’s father, Fearne’s great-grandfather, Evan Meredith.

Evan, a coal miner, was about 18 in the photo, which makes Fearne wonder what her great grandfather did in the First World War. Fearne’s dad says this was never spoken of in the family, either by Ruby or Evan himself. Using the birth records on TheGenealogist we can find Evan’s birth recorded at Bedwelty in South Wales in the year 1896.

To find out more about Evan, Fearne heads to Abertillery, in Wales, where he had worked in the mines from the age of 13. We are able to find him, aged 15, along with his miner father, his mother and his siblings in the 1911 census on TheGenealogist.

At the Llanhilleth Miners’ Institute, Fearne meets up with mining historian Ben Curtis who tells her that at the beginning of World War I in 1914, coal mining had been a crucial part of the war effort and so miners were in a designated reserved occupation. As the war dragged on, with the slaughter on the battlefield meaning that more and more men were needed to fight the enemy, the Government set its sights on ‘combing out’ 50,000 single men from Britain’s collieries for conscription. That was to include 5% of the miners in South Wales who would be compulsorily enlisted to fight the enemy rather than dig coal. Fearne thinks that her great-grandfather was probably one:

My gut’s saying he probably ended up going to war

Ben, however, has unearthed a newspaper article from July 1918 that reveals that Fearne’s great-grandfather, had been a Conscientious Objector, and was arrested by the police. She is upset and asks:

‘Does that mean that they would’ve been called up to the Army but refused? And then [they] were essentially arrested?

Evan Meredith, it turns out, was handed over to an Army escort for refusing to fight and was taken away to prison.

I guess I’m quite shocked to hear about Evan’s refusal to join the Army. I doubt that it’s just… a simple act of rebellion so I really want to try and understand more about his decision-making and the impact that had

At Brecon Barracks, where her ancestor had been taken after his arrest, she meets the historian Aled Eirug. He is able to tell Fearne that Evan was sentenced to six months imprisonment and Fearne gets another shock when she finds out that her great grandfather served this sentence in Wormwood Scrubs Prison in London. Another document that Fearne sees reveals how Evan was classified as a ‘category B’ conscientious objector- that is someone who most likely opposed the war on political rather than religious grounds. Some conscientious objectors, Aled explains in the Who Do You Think You Are? episode, saw the conflict as a capitalist war which had nothing to do with the working-classes and this was a point of view held by many in the mining community of South Wales.

The coming of peace in December 1918 did not mean Evan’s incarceration came to an end. Despite his sentence in Wormwood Scrubs having been served in full Fearne discovers that, rather than being released, her great-grandfather was immediately re-arrested! He was taken back to Wales where he faced another court martial a controversial measure, given that the war was over.

Fearne finds out that six months after the Armistice, in the spring of 1919, Evan was still an inmate, though this time in a Carmarthen prison.

On one hand, I massively admire Evan’s courage and his strong-willed ways and the fact that he vehemently stuck to his moral reasons as to why he didn’t want to go to war… Then, on the other hand, so many families… lost relatives at war in the same area, and that’s unbelievably heart-breaking, so it’s really hard to digest it all and work out how I feel

Fearne meets the historian Lois Bibbings in Carmarthen who has found a prison record for Evan Meredith that details his time at Carmarthen Prison. Fearne finds out that once Evan had been rearrested in December 1918, he was taken back to Wales to face a second court martial, and this time receive a sentence of one year’s hard labour at Carmarthen Prison. Lois explains to Fearne what Evan would have had to go through in prison as a conscientious objector and that included the ‘silence rule’ that prevented him from communicating with the other prisoners.

Access Over a Billion Records

Try a four-month Diamond subscription and we’ll apply a lifetime discount making it just £44.95 (standard price £64.95). You’ll gain access to all of our exclusive record collections and unique search tools (Along with Censuses, BMDs, Wills and more), providing you with the best resources online to discover your family history story.

We’ll also give you a free 12-month subscription to Discover Your Ancestors online magazine (worth £24.99), so you can read more great Family History research articles like this!

Fearne is confused by a document that she reads which shows that he was temporarily discharged in the summer of 1919, some months before his sentence was supposed to end. Lois is able to help as she has found a published history of the wider Meredith family. Within this is a chapter written by Evan, in which he recalls his experiences as a prisoner. In this account he explains that he had organised a hunger strike in Carmarthen Prison in a bid to pressure the authorities into releasing him and other Conscientious Objectors.

Evan noted that after four days of returning their meals untouched, he was released under the ‘Cat and Mouse Act’. ‘The Prisoners, Temporary Discharge for Health Act’ was a way for the authorities to avoid force-feeding prisoners on hunger-strike. By allowing weakened prisoners, who were in danger of dying, early release they could then be rearrested once they had recovered sufficiently. Lois is able to explain to Fearne that there was no evidence that Evan had been rearrested after his release and so was probably free to return home. Being able to read Evan’s own words is a boon for Fearne.

What’s clear to me already is… that he didn’t want to go to war because he didn’t want to kill anyone. It’s that simple really. I’m really getting a picture of who he was. It’s really, really special to read his words

To try and make more sense about Evan’s life, Fearne is seen on the screen going to visit Evan’s son. Her great-uncle Hadyn is now a 93-year-old living in Lymington and in an emotional scene, they talk together about Evan’s time as a prisoner during the First World War. Hadyn says that his father never spoke of it because it was considered deeply shaming. Her great-uncle also helps Fearne to understand Evan’s life after the war. He explains that Evan managed to get out of the mines, educated himself to become a pharmacist and was eventually awarded a Fellowship of the Pharmaceutical Society. Fearne is moved by hearing Hadyn talk about his father with such pride:

It was really quite emotional talking to Hadyn. There was this huge sense of pride about where his father had come from and where he’d ended up. I can’t help but feel completely bursting with pride about that

Fearne Cotton’s maternal roots

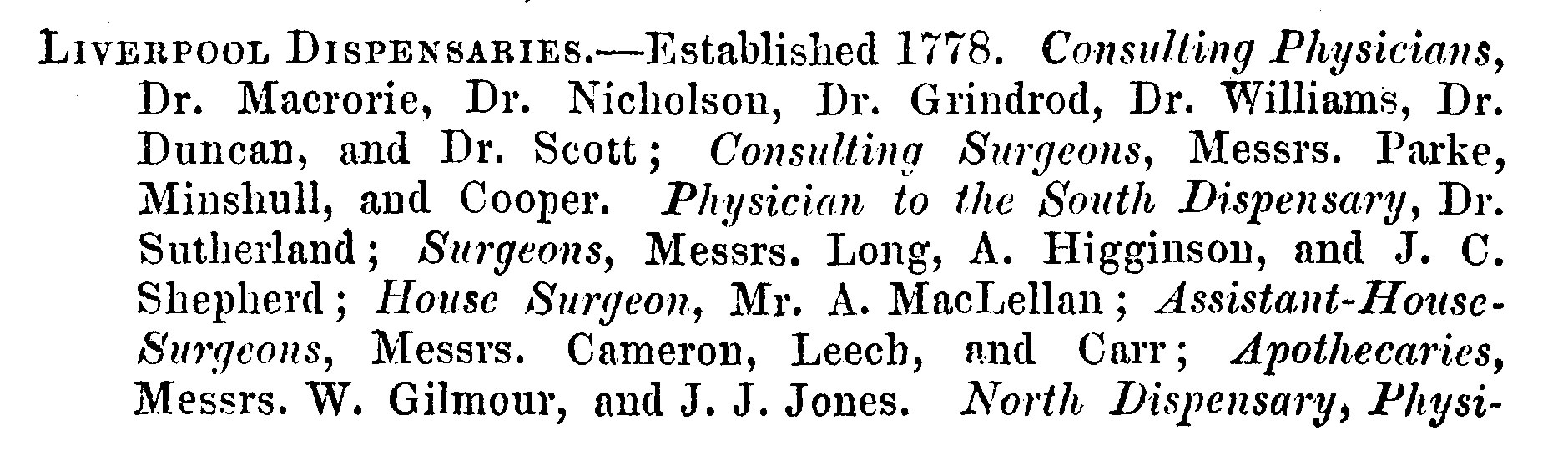

After unearthing Evan’s story, from her paternal side of the family, Fearne is able to get the help of genealogist Laura Berry to find out more about her maternal line. She knows very little about Linda’s forebears and so Laura is able to tell her about many ancestors of Fearne that lived in London, Suffolk and Essex. The surprise for Fearne is, however, that her 4 x great-grandfather, William Gilmour, was born around 1821 in Garvagh in Ireland (now in Northern Ireland). Fearne is delighted to find this out and so the TV programme sees her heading off to Garvagh to see what more she can discover about him.

I’ve never ever heard about Ireland being connected to my family in any way at all, so that’s really surprising

In Garvagh, Fearne joins historian Elaine Farrell at the local museum. By consulting a local newspaper article that had been published in 1844, it becomes clear that William moved from Garvagh to Liverpool when he was around 23. In Liverpool he found work as a chemist and druggist until, ten years after leaving Ireland, William went back to Ireland. He was now practicing as a doctor in Coleraine, close to Garvagh.

The records show Fearne that when he went back he brought along an English wife, Elizabeth from Buckinghamshire, and a young family. The research then reveals that in about 1856, just a year after returning to Ireland, William Gilmour is next to be found working onboard the ‘SS Great Britain’. The ship was on charter to the government as a troopship, at this time, as it sailed to and from the Crimea. William Gilmour was the ship’s Medical Superintendent and as such he was responsible for the welfare of all those who sailed on her. Fearne’s opinion of her ancestor’s decision to go to sea is uncompromising:

I mean, if that were me, and I’d not only moved from where I was born but had just settled and I had young kids – I’d be livid. I don’t care about your certificates and your career – you’re staying here. Staying put. Get back in that surgery. I’d be very angry.

A visit to Bristol, where the SS Great Britain is now in dry dock, enables Fearne to find out more about her 4x great-grandfather’s work on the ship. The naval historian Andrew Lambert is able to explain that William Gilmour’s job would have been difficult and dangerous. He would be treating soldiers that had succumbed to cholera and dysentery, tending to their battle wounds, and performing amputations of limbs in cramped conditions.

Access Over a Billion Records

Subscribe to our newsletter, filled with more captivating articles, expert tips, and special offers.

But the research has unearthed a secret. Fearne now discovers from Andrew that William appears to have exaggerated his qualifications in order to get this job.

What we’re looking at is a classic example of Victorian social progress. It’s all about taking a chance, finding another way of getting on

Despite this subterfuge William was able to pull it off. Fearne sees a newspaper testimonial that praises her 4x great-grandfather’s unstinting work on the ship. What delights Fearne is to also discover that after Queen Victoria visited the SS Great Britain, her ancestor was sent a special invitation to come on board the Royal Yacht for lunch in recognition of his excellent work.

It’s the ultimate success story. Someone who came from really quite humble beginnings then had this vision, had this idea and made it happen

It doesn’t get any better than that. What he did was incredible, an amazing feat and huge success… and there he is, on a yacht, having lunch with Victoria. Fab!

William Gilmour’s service at sea didn’t end there. After the Crimea, William continued to work as a Medical Superintendent at sea, this time onboard the passenger liner the Royal Charter. In 1859 he resigned from being a ship’s doctor stating his intention to “commence the practice of my profession here in Aylesbury. I may succeed and may not”. The TV programme sees Fearne expressing her pleasure at this turn of events:

That makes me feel relieved. So he’s set up there, he’s got his new practice, the wife’s happy, his days on the sea were over. That’s a relief!

TheGenealogist’s occupational records include William’s entry in The Medical Register 1861 that shows his date of registration as 1st January 1859 with his qualifications dating to 1854 and 1860.

Fearne’s next meeting is in Aylesbury with the historian Elaine Thomson. Visiting the house from which William conducted his private medical practice and lived with his wife and children, Fearne learns that Aylesbury wasn’t such a smart move for him. Just a few years after settling there William Gilmour went bankrupt. He suffered the indignity of having all his belongings auctioned off at his own house so that he could pay his numerous debts.

Fearne is able to learn that William was not to be perturbed by this setback as within weeks he was employed as the District Officer for the Ongar Poor Law Union. This move, with his family in tow, was quite a step down for the Doctor. Nonetheless Fearne admires William for his tenacity.

I like that he doesn’t give up, I like that a lot. Persistent. That trait’s in our family, for sure

Fearne is able to visit Ongar, in Essex, and see the building that old Ongar Workhouse, where William would once have worked from. At the workhouse she is able to talk to historian Peter Higginbotham, who specialises in the history of workhouses. Peter explains that as a District Medical Officer, William would have visited the poor in their own homes to provide medical help to them. If he was not able to attend himself then it was up to him to find cover. It seems that was not always able to arrange that and in 1871 he was called before the Board of Guardians of the Ongar Poor Law Union to answer a charge of neglect. Tragically a child had died after William, who had been unwell himself, had neglected to pay her a visit and had failed to find any cover for himself.

Shortly after this disastrous event, William left Essex and turns up next working at the Bethnal Green Workhouse as the dispenser. It seems that his money troubles had worsened and he had requested to be paid weekly. Sadly, for Fearne’s 4x great-grandfather he falls ill himself and is unable to work. His death in 1881, aged only 60, was from a common workhouse disease: bronchitis and his wife Elizabeth was present at his demise. The death index records on TheGenealogist show that it was in the first quarter of 1881 in Bethnal Green, Middlesex.

He had such high hopes and he kept on trudging and battling away… he finished his life in quite a humble way – as it had started. Good story, though. He had a great story. He definitely wasn’t boring (laughs). That’s for sure. Definitely wasn’t boring

From Evan Meredith, the coalminer who endured prison for his anti-war views and who became a chemist, and William Gilmour, who strived to improve his lot in the world, Fearne is pleased that her family story has found the work ethic and drive that she hoped to discover.

Though the accounts of her ancestors lives revealed some mixed fortunes for them, Fearne is pleased to have discovered family history tales that she can pass on to her own children:

I really want my kids to understand these brilliant stories when they get older, and see the determination and the grit and the passion there

Sources:

Press Information from IJPR on behalf of the programme makers Wall to Wall Media

Extra research and record images from TheGenealogist.co.uk

BBC Images